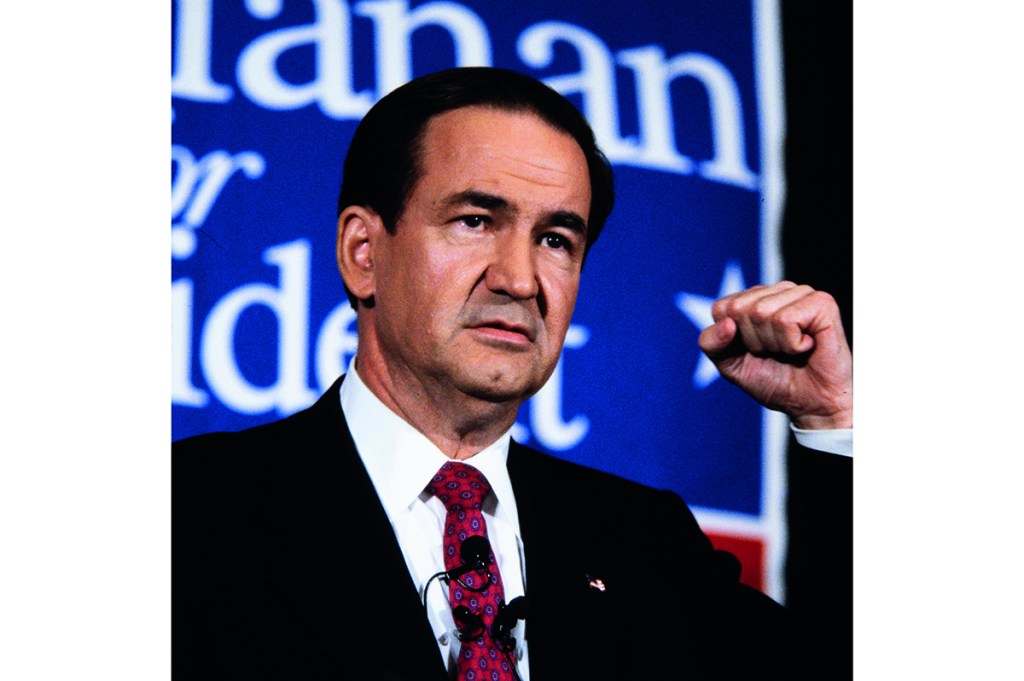

It was a relatively cool 85 degrees in Houston on the August evening thirty years ago when Republicans gathered at the Astrodome to renominate George H.W. Bush for the 1992 presidential election. The opening session’s speakers included Senator John McCain, Stanford professor Condoleezza Rice, and re-election campaign co-chairman Ken Lay, later to gain fame as a major figure in the Enron scandals. But the speech that would be the most memorable by far was delivered by a television commentator, syndicated columnist and former Richard Nixon hatchet man — the fifty-four-year-old Irish Catholic Pat Buchanan, who delivered what came to be known as “The Culture War Speech.”

Buchanan, who had mounted an insurgent primary challenge from the right, had made the president sweat in the early going in New Hampshire, where Bush’s break from his “Read My Lips: No New Taxes” pledge came to symbolize voters’ concerns about the economy. Buchanan’s shoestring effort was doomed from the beginning, but the message he delivered that night in Houston was met with raucous populist applause for “Pitchfork Pat.”

As he approached the end of his remarks, his voice dropped to a hush, and he spoke in a more serious tone than he used on The McLaughlin Group, as he said:

My friends, this election is about more than who gets what. It is about who we are. It is about what we believe and what we stand for as Americans. There is a religious war going on in this country. It is a cultural war as critical to the kind of nation we shall be as was the Cold War itself, for this war is for the soul of America…

My friends, these people are our people. They don’t read Adam Smith or Edmund Burke, but they come from the same schoolyards, the same playgrounds and towns as we come from. They share our beliefs and convictions, our hopes and our dreams. They are the conservatives of the heart. They are our people, and we need to reconnect with them. We need to let them know we know how bad they’re hurting. They don’t expect miracles of us, but they need to know we care.

What’s fascinating about Buchanan’s culture war speech three decades on is how little it has to do with what are typically considered “culture war” issues by the media complex. Abortion and gay marriage receive scant mention; gun rights none at all. Buchanan instead spent far more of his speech talking about jobs, spending and environmentalism. He closed with a fervent image of the violent Los Angeles riots of that spring.

The culture war battles of 2022 echo this dynamic. Democrats, who view the Supreme Court’s decision overturning Roe v. Wade as a political lifeline, want to define the culture war according to a familiar trio: abortion, guns and gay marriage. But for Republicans — and, they hope, for most independent voters — the culture-war issues of the day are very different. They are about crime and policing, a border that’s out of control, an economy that doesn’t work for the middle class, a radical trans agenda and a race-focused education regime. The forgiveness of student loans by President Joe Biden’s White House is a culture-war issue, too, as are the increased leftist pressure campaigns weaponizing Big Tech and corporate America against conservative Americans, including their own workers.

The Democratic effort in 2022 is to limit the conversation about the culture wars to the definitions of the past. They insist that Critical Race Theory isn’t taught in schools and that gifted programs are racially biased; that sacrificing jobs for the good of the environment and tax dollars for electric-car subsidies is the height of morality; and that only bigots are offended by men dancing provocatively for schoolchildren or changing in girls’ locker rooms before they beat them by half a minute on the racetrack or in the swimming pool. Above all, they claim that no one anywhere ever really wanted to Defund the Police — and that you are lying if you say otherwise.

This form of culture-war erasure — deployed in these midterm elections by Democrats hoping to distract from dire concerns about the economy and inflation — is unlikely to convince the electorate that Republicans are too radical on cultural issues to govern. It requires acceptance of the left’s views on education — that teachers, not parents, know best what young children ought to be taught about America’s racial history. It insists that voters believe the new Democratic spin on policing and on the border crisis — that their condemnation of the January 6 riot makes them the defenders of law and order. And it demands that voters accept that a man can become a woman — which, frankly, does not fly with the multiethnic, immigrant-heavy Democratic majority that their party once envisioned.

This is true of many aspects of the Democrats’ approach to the culture-war issues of 2022. They have doubled down on the new recruits of the Donald Trump era: their dominance among women, particularly college-educated white women. Virginia’s 2021 gubernatorial race provided an example of this enormous divide: Fox’s voter screens found that 54 percent of white college-educated women backed Democrat Terry McAuliffe, while 68 percent of white women without college educations voted for the winner, Republican Glenn Youngkin.

In doubling down on abortion, tax redistribution for student loan forgiveness and electric vehicles and an ultra-progressive race and gender educational agenda, Democratic talking points are music to the ears of these suburban white women voters. They are the sort who spend upwards of $2,500 to hire Saira Rao, a leftist activist and failed congressional candidate, to host dinners where they learn to accept and admit how racist they are over vegan hors d’oeuvres and white wine.

Rao’s been hosting these dinners since 2019, the same year she tweeted “The American flag makes me sick.” The stars and stripes do the same to Colin Kaepernick, the former NFL quarterback and famous kneeler who reportedly influenced Nike’s cancellation of a Fourth of July-themed shoe featuring the Betsy Ross flag. Someone at the FBI agrees. In 2019, they published a “Domestic Terrorism Symbols Guide” which included the Betsy Ross flag and the Gadsden flag — which you’ll find flying in many American towns and even on government-issued license plates — as signifying potential revolutionary or militia intent. Under questioning from Texas senator Ted Cruz, FBI director Chris Wray denied knowledge of the instruction.

What we are witnessing is a clash of priorities. In the context of 2022, Republicans feel bullish on the vast majority of their culture-war stances. But Democrats hope that they can fend off the election wave that history and most polling indicators suggest is incoming with an appeal to one priority above all the others: abortion.

On this count, there is plenty of evidence via the behavior of Republican politicians to suggest the Democrats are correct. The Dobbs decision, despite being long-anticipated and even leaked in advance, seemed to take elected Republicans by surprise. Though they’d been used for decades to discussing the abortion issue in the context of judicial nominations or government funding, Republicans were suddenly uncertain about how to proceed. Pro-lifers were dealt a blow when a confusingly worded Kansas abortion amendment went down to defeat with significant opposition from GOP voters. And when South Carolina senator Lindsey Graham proposed a nationwide federal ban on abortion at fifteen weeks, Democrats trumpeted it as an indication of Republican extremism.

In truth, of course, it is the Democratic Party that is wedded to an extreme position on the abortion issue. Polling consistently bears this out. Their Senate candidates for 2022, to a person, advocate for no limitations on abortion at any point in pregnancy. And their earlier legislative effort, branded as an attempt to “codify Roe,” would actually strike down virtually all state limitations that withstood legal challenges prior to Dobbs.

Graham’s proposal, while constitutionally questionable, is based on the same fifteen-week mark maintained by the Mississippi law at question in Dobbs — which is perhaps to the left of the median American on the issue. A July poll by the Republican firm OnMessage asked “Do you support or oppose a law that would restrict abortion after the baby develops a heartbeat, with an exception if complications threaten the life of the mother?” They found 41 percent opposition and 55 percent support. The medical assertions of Georgia’s Stacey Abrams aside, most heartbeats are detected in the womb at around six to eight weeks.

If Democrats fail in 2022, it may be because they fell prey to the temptation to fight the last culture war instead of the current one. They failed to recognize that rather than having to find the culture war outside the local Planned Parenthood clinic, voters of today see it everywhere. They see it at work, in their children’s classrooms, on city streets, with messages emblazoned across social media and in the NFL’s endzones. The culture war surrounds them, envelops them and frightens many of them, with jobs granting little in the way of status or security even as their salaries buy less and less. The fear of cancellation was once the concern of the prominent — now, it can happen to anyone, anywhere, at any time. The wrong word expressed in the wrong context can unperson you in a matter of hours. And most Americans know it.

This reality is one Buchanan’s speech anticipated. There have always been cultural battles, but today’s largest one had yet to appear in 1992. Buchanan referred to it in the context of pro-life Pennsylvania governor Bob Casey, of Planned Parenthood v. Casey, being denied a speaking slot at the Democratic National Convention — there was “no room at the inn” for pro-life Democrats. The increasingly partisan nature of these cultural issues would in the coming years dramatically reduce the number of conservative Democrats and push traditionalist Americans, gun owners and churchgoers into the Republican coalition.

The trends of the past few decades illustrate a major reason why nothing can get done in Washington anymore. With culture wars taking primacy, it is virtually impossible for bipartisan legislating to accomplish much of anything. If senators lack agreement about when life begins, what marriage is, whether a man can be a woman and what schools should teach children about all these things, it makes it that much harder to meet in a room and settle on taxation levels and healthcare policy. Working with the other side doesn’t mean the same thing it used to mean.

Buchanan’s speech closed with a call to conventiongoers to emulate the National Guard in the LA riots — to “take back our cities, and take back our culture, and take back our country.” It is a warlike metaphor, and it played to that crowd. For traditionalists who saw the country being stripped away as the Greatest Generation gave way to the leadership of baby boomers, it was a message based on nostalgia for a time of duty and service to something other than self. But it was a message for a time that was past.

After Buchanan’s culture-war speech was finished that Houston night in 1992, the evening ended with moving words from former president Ronald Reagan, in what would be one of his last public speeches. He urged the nation on with his trademark optimism. “Whatever else history may say about me when I’m gone,” he said, “I hope it will record that I appealed to your best hopes, not your worst fears, to your confidence rather than your doubts.” This may well be an expression of the Republican message of the Reagan era — but it is not the message for 2022 for either party. Here, in this election, we find only fear and doubt about an uncertain future, and a culture war that, despite all hopes, may never end.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s November 2022 World edition.